That's the message delivered during a keynote discussion titled, "3 Steps to Ensure Operational Integrity," presented at the Schneider Electric's 2015 Global Automation Conference by Scott Mourier, global process automation SIS expertise area leader, Dow Chemical Company, and Andre Ristaino, managing director, Automation Standards Compliance Institute of the International Society of Automation.

During the presentation, Steve Elliott, senior director, offer marketing for process automation, Schneider Electric, moderated a conversation between Mourier, representing the user-side safety perspective, and Ristaino, the standards-side security expert. Together, they provided a framework for assessing safety and security's impact by presenting three questions that all suppliers, integrators and asset owners must ask:

- Do we know what could go wrong?

- Do we know what our systems are to prevent this from happening?

- Do we have the information to assure us these systems are working effectively?

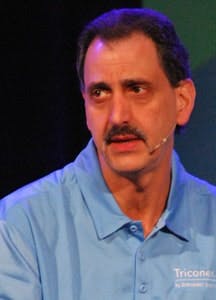

"Tomorrow's risks will be different." Scott Mourier, global process automation SIS expertise area leader, Dow Chemical Company, speaking at Schneider Electric's 2015 Global Automation Conference in Dallas.

While safety risks are well established through years of experience, the same cannot be said for cybersecurity, a young field in which even the most up-to-date awareness can provide only a view of the risks that existed yesterday."Tomorrow's risks will be different," said Mourier.

"It's unfortunate that [with safety] we learn through accidents and incidents; the standards have evolved to address these," said Mourier, who laid out the process his company follows. "The standard that we follow as a user company is IEC 61511, which lays out the safety lifecycle."

In practice, it looks like this: "Start with a process design, and the design will drive the identification of the hazards," Mourier said. "Then you go through the consequence analysis. As you do that analysis, you define your specific areas of protection. You identify the risk, how the risk gets mitigated and as you go through these, you determine the level of integrity you require. As you do all these things, it ultimately drives your design."

"If you substituted the word ‘security' for ‘safety,' you'd pretty much be there," Ristaino said of Mourier's explanation. "The security lifecycle is very similar to the safety lifecycle. The only thing that's missing for security is that we don't have 35 years of maturity in the security paradigm."

What we do have, Ristaino said, is ISA 62443. "That's the reference starting point for assessing what could go wrong. You can't do anything if you don't have a known starting point. So we start with this: Are the products secure?" These standards, Ristaino said, provide measurability that can be missing from suppliers' answers to that question. "‘Really, really secure' isn't good enough," he said, pointing to the importance of TUV's safety and security certifications.

Working their way up the lifecycle from suppliers who design and manufacture the COTS control systems through the engineers who integrate them into site-specific systems, to the asset owners who operate and maintain them, Mourier and Ristaino showed how safety and security need to be aligned across technology, processes and people, and between business and operations.

"We need to move safety and security out of their silos, because often security issues are safety issues," Ristaino said, adding that security incidents that can lead to safety emergencies can as easily be accidental and internal as they can be malicious.

"This isn't about technology," Ristaino said. "It's about people and procedures. It's about having a shared vocabulary where the same words have the same meanings. We need to make the same commitment to security that we have made to safety."